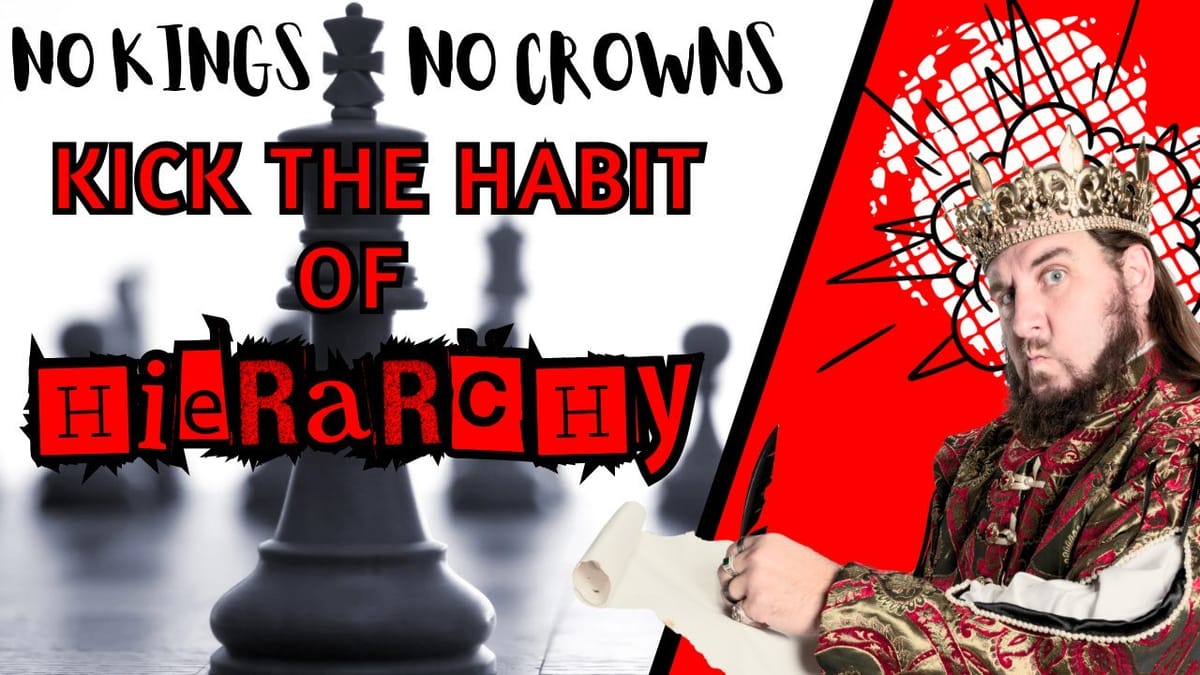

No Kings. No Crowns. Kicking the Habit of Hierarchy

Hierarchy, in our society, is not usually a conscious choice.

Why did France fall into the tiny hands of the original Napoleon complex after all the liberte of the French Revolution? Why did the fledgling Weimar democracy crawl into the power of a heinous man who made the mustache more sinister than it was ever meant to be? And why did the most recent US presidential election put the world’s most powerful country under the leadership of a spray-tanned wanna-be-despot with less class than the back airplane seat across from the toilet?

“I’m finding that this trend can be expressed in one word… hierarchy.”

Prefer watching? This essay is available in video form.

Many would argue that our social woes are a psychological phenomenon. That our societies are perpetually on the relationship rebound, swiping through dregs of a proverbial political Tinder for the next toxic alpha male. I think this theory has validity.

But I would also argue that this trend toward totalitarianism is even bigger than a societal trauma reenactment of the “father wound.” I’m finding that this trend can be expressed in one word.

A word that encompasses everything from monarchy and patriarchy to oversimplified, reductionist scientific models that have been used to justify humans objectifying everything from plants to animals to each other to our own brains. That word is hierarchy.

The most basic definition of hierarchy is “a graded or ranked series.” Which could be fine if we’re just ranking something straightforward like which fish are larger than other fish. But the fact is, we live in societies of dominance hierarchy, societies where some humans are given significantly more value and power through structures of inequality. In societies like this, it’s easy to apply that same perspective to any hierarchical model. We tend to treat any ranking as a hierarchy of not only specific traits but also of power and value—of better and worse—greater and lesser.

Like a bunch of bros taking fish pics, we can easily assume that the heaviest fish is the BEST fish, the manliest fish. And not only does that kind of thinking make us act very silly, it’s actually connected to the same type of objectification, the denial of interrelatedness, that might lead a person to kill a fish without any intent of eating it or even selling it. Because real apex predators hunt for sport but eat at McDonalds. I digress.

“Hierarchy is so ingrained into our brains that we see hierarchies everywhere, even where they don’t exist in the first place.”

Hierarchy is so ingrained into our brains that we see hierarchies everywhere, even where they don’t exist in the first place. And when we see a hierarchy, we immediately start assigning ranks of value and power as if they are absolute or inherent. I see two huge problems with this. One, this kind of thinking can be used to justify the dominant power structures in our societies. And two, the very nature of vertical, stratified rankings emphasizes the connections between the things or people that we’re ranking. In short, hierarchy is not only a structure of dominance, it’s also a structure of loneliness.

Hierarchy, in our society, is not usually a conscious choice. It’s something we’re born into—from power structures to belief systems. It’s a habit we inherit—a habit that has become unconscious and therefore hard to break. A habit that separates person from person and separates human beings from our environment. A habit that allows us to believe we are lesser than or greater than. A habit that subjugates societies not just through external structures but also through our own internal beliefs. A habit of placing people above animals—some plants lower than other plants—some races higher than other races—and certain skills and traits above other skills and traits. A habit that keeps us crawling to kings and grasping at crowns.

Hierarchy originally meant “the rule of a high priest” and also referred to hierarchies of angels (etymology). I’m not here to argue about angels—how many can dance on a pin or otherwise—I’m here to point out how this habit of hierarchy permeates our entire worldview—the way we see the physical, spiritual and everything in between.

What is politics?

Prefer audiobooks that also support indie bookstores? Check out Libro.fm here.

To kick a habit, we first need to identify where it shows up, how we acquired it, and why it’s unhealthy. That way, involuntary unconscious thinking becomes conscious. So that’s where I’ll start—pointing out the habit of hierarchy in outdated worldviews that are still prominent today.

Hierarchical models are usually represented in vertical diagrams, typically linear and triangular—from food chains to chains of command to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and the carb-saturated food pyramid. But there are some glaring issues with these models of thinking. First, it's too easy to see a hierarchy as an absolute measure of inherent value and power—sure an eagle (the top of the food chain) is physically stronger and faster than a mouse and will eat it—but mice as a species are actually stronger than eagles in terms of their ability to adapt, reproduce, and endure adverse conditions. Value and power depend on the criteria of our judgment, they are not absolute. And ultimately, eagles and mice are interdependent in terms of a given ecosystem.

A more accurate food chain mode is a circle that illustrates a cycle where the predator’s body will nourish plants as it decomposes—the circle of life. An even more accurate model is a food web that allows us to show more complex interrelatedness in an ecosystem without placing any one creature at the top or the bottom.

And this habit of hierarchy is much older than the linear food chain model. For centuries, Western scientists placed all plant life into a hierarchical taxonomy, a “great chain of being” that categorized life into higher and lower plants and beings (overview). Human beings, of course, occupied the top of this chain, or ladder according to Aristotle, positioning humans as the rulers of all taxonomy and the crowning achievement of evolution, neatly justifying and perpetuating the use and abuse of other species in our service.

Yet even within our “highest of species” the habit of hierarchy separates one human being from another. This is the authoritarian idea that we need order to be imposed in a top down structure—the belief that power inequality is a necessary evil to maintain social order, or even beneficial to the form and function of society.

This type of social hierarchy was the norm in Ancient Greece, where Plato described divided classes of—rulers, soldiers, and producers (summary)—a framework that not only differentiates roles but also assigns hierarchical value and power. Of course, many ancient civilizations had similar societies, but Ancient Greece is particularly relevant here because it was the specific culture that Western European society has referred to as a basis of operation and justification—ideals that spread through colonization to form the basis of many contemporary assumptions and habits about the nature of humanity and the nature of nature itself.

Nature is certainly full of ordered societies and structures with specific functions, like bee hives, but are these hierarchies? While bees have different functions in a hive, no bee is truly higher or lower in value or status—they are interdependent. In fact, 20th century scientists gradually realized that bees even share a common “hive mind,” a deeply interconnected collective consciousness (Thomas Seeley / collective decision-making). Yet, we still use the term “queen bee,” reflecting an old hierarchical mindset. In fact, humans at least as far back as, once again, Ancient Greece assumed this “ruler bee” was a male, a king bee, a misconception that was perpetuated for almost two millenia (historical note). This reveals a lot about the way humans have projected hierarchy (and patriarchy) onto the world around us.

“Value and power depend on the criteria of our judgment, they are not absolute.”

This same hierarchical thinking is also perpetuated with Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs,” which defines needs such as physical health and security as more essential than non-physical needs such as love, esteem, and creativity. To be sure, humans will die without food and water, but many have also died from lack of love and self-fullfillment. The fact is that human needs and abilities are not separate, but deeply interconnected. Love and creativity are not just aftereffects of survival, but are essential for humans to meet our basic needs in efficient and sustainable ways.

If you exercise your creativity, you could build a better shelter and if you have love in your life, the people who love you could help you. But there are way too many people quoting Maslow’s hierarchy to say that we need to meet our basic needs first before we worry about something as non-essential as creativity or love. To be fair, Maslow tried to emphasize that human needs are interconnected, but the way he presented his model, as a hierarchy, plays right into our habit of hierarchical dominance, especially due to the pyramid visual that was introduced a few decades later by Charles McDermid (history of the pyramid).

If we place a human trait like creativity on a pedestal as an apex achievement, we can easily overlook how foundational and interconnected it is to all our other capacities. And to me, this demonstrates that while the top of a hierarchy may be a privileged place—it is in fact a lonely and restrictive distinction–because one of the most harmful aspects of a vertical hierarchy is a denial or deemphasis of interrelatedness.

This is especially true with misconceptions of our own brains that are still quite popular today. The triune brain theory, put forth by Paul MacLean in the 1960s, basically applied Plato’s social model of intellectual rulers above spirited warriors above physical laborers to create a hierarchical model of the brain. This theory neatly separated the brain into three regions that presumably evolved separately over time: the reptilian or physical brain, the limbic or emotional system, and the neocortex or higher thinking (Barrett, 2021). The myth of the triune brain is still perpetuated today despite the fact that this theory of brain evolution and function has been disproved for many years! I still see this myth floating around in schools and internet articles, and I myself was quoting this theory until embarrassingly recently.

The triune brain theory has historically valued critical thinking as quite literally the highest achievement of humanity, devaluing emotions as secondary, and physical knowledge as simply primitive. This hierarchical perspective of our human capacities has undervalued emotional and tacit knowledge and greatly underestimated how all forms of knowledge, all ways of knowing, are integrated and interconnected. This has also enabled humans to objectify more “primitive” animals and therefore exploit them through sport hunting, experiments, and overall ecological destruction.

Scientists have been learning that what makes our human brains so powerful is not hierarchical compartmentalization, but an interconnectedness that is deeply intricate and embodied. The complexity of the brain is what allows us to be creative, resilient, and intelligent. Much like the bees in a hive, each seemingly separate part of the brain forms a united whole. Instead of speaking of a triune brain, it is more accurate to speak of the adaptive brain. Considering the brain as adaptive “emphasizes the interdependence and plasticity of brain regions and the brain's ability to predict and adapt to future needs and conditions” (Steffen et al., 2022).

The replacement habit

Yet, even as vertical hierarchies are replaced with more accurate and dynamic systems models in sciences from ecology to neurology, the habit of hierarchy is still the basis of most of our social and economic organization and also the basis of how many people make conscious or, more often, unconscious decisions in daily life. So how do we kick the habit of hierarchy?

Kicking the habit of hierarchy isn’t as simple as dethroning kings, though we can do that too. Once we identify a bad habit, we also need to form a new one, a replacement habit if you will. Since hierarchy is a structure of loneliness, I suggest the replacement habit of relationships—the habit of forming and finding relationships between ideas, people, and ecosystems. This habit replaces rigid linear ways of thinking and living with complex interrelated systems like webs. These webs are not only relational, they’re also more dynamic, more interesting, more resilient, and even more effective.

It’s hard to talk about “relationship” in human systems without sounding generically utopian, which I think demonstrates how badly hierarchy has affected our thinking. So rather than talking about anarchist theory, I’m going to approach this habit of relationship through a story—a story that demonstrates relationships and connections between real people and cultures and their ideas: This is the story behind Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. I got most of this information from a talk by a Blackfoot community member, Ryan Heavy Head, director of Kainai Studies at Red Crow Community College (talk). I encourage you to watch it, but I want to summarize a few crucial points of this story because this story demonstrates the contrast between hierarchical and relational thinking better than I ever could.

The story begins with an eager academic named Abraham Maslow. Maslow wanted to study the trends of sexual and physical dominance that psychologists were observing in primates to try to understand power, self-esteem, and social organization, in other words ALPHA MALES, which were all the rage, largely thanks to good-old Freud.

But his teacher and mentor, a woman named Ruth Benedict, did not agree with this assumption of dominance hierarchy, so she suggested that Maslow go spend time with the Blackfoot Siksika in Alberta, Canada. So Maslow arrived with his psychological questionnaire in hand. And when he proceeded to ask the Siksika elders about their dominance over others in their communities and their sex lives, they were rightly horrified.

The Siksika community was not and is not a dominance hierarchy, but rather a community of interconnection and cooperation—where authority is earned and revocable—where children are respected like adults—where decisions are made through discussion and agreement—where wealth increases status only when given away.

Maslow’s concept of self-actualization came out of his time with the Siksika, where he observed that 80–90% of the Blackfoot people had a quality of self-esteem that was only found in 5–10% of his own population (Heavy Head talk; also discussed in this write-up). So then, what does this self-acutalized community have to say about the hierarchy of needs that Maslow perceived in their culture?

Ryan Heavy Head emphasized that while Maslow’s time with the Siksika was transformative, and while Maslow left them with a more open mind and new revelations, his findings ultimately revealed his own cultural bias and the lens through which he saw the world. A lens of hierarchical individualism.

Ryan concluded that what Maslow and many other Westerners do not see or understand about his people is their value of relationship—relationship to the land and relationship to one another. These are ties that are not replaceable or disposable. These connections and relationships are the foundation of a worldview, a societal structure, and a method of thinking that are based in relational synergy—in the efficiency, resiliency, and power of relationships.

“We need to embed knowledge in human stories.”

To well and truly kick the habit of hierarchy, we need to recontextualize ideas like Maslow’s hierarchy in real places, in real human stories and cultures, in real relationships between real people. We need to embed knowledge in human stories—like the story of the Siksika people—a story completely absent from Maslow’s Wikipedia page and most iterations of his biography by the way. We need to get information out of silos and reductionist models. We need to find connections and relationships, even and especially where they don’t seem to exist.

And of course, we also need to get people out of human silos. As corny as it sounds, we need to get to know our literal neighbors, the people who live next to us, and we need to become curious about their lives and their stories.

We also need to build organizations and movements that are built on relationships rather than lonely hierarchies. This can look like forming workers unions, co-ops, restorative systems of justice, and grassroots movements. And on a smaller scale, which is no less important, this can look like families and schools replacing coercive dominance structures with value-based relationships and restorative practices.

When a group or organization is based on strong relationships rather than a rigid dominance hierarchy, structure is not maintained by coercive rewards and punishments, and instead, peer accountability can grant and even revoke authority, and group decisions could be made through collaboration and even consensus. Power can be decentralized through shared-ownership like co-ops or through a network of roles defined by responsibility rather than a system of rank.

I don’t know of any organization that does this perfectly, but I don’t know of any utopian hierarchies either. That’s not the standard I judge humans by... because we’re humans. But I will share a few examples or organizations that have kicked aside hierarchical habits to different extents and in different ways—organizations demonstrating that relationship is actually a better, more productive habit than rigid hierarchy.

Patagonia (a global outdoor apparel company) keeps leadership intentionally light and gives teams wide autonomy, showing that strong values can coordinate work without heavy control (Patagonia ... Let My People Go Surfing on Libro.fm).

. Leadership exists but it’s understood to be situational and constrained, not positional.

Mondragón (a massive Spanish federation of worker-owned businesses) ties authority to ownership: workers elect leaders and cap pay ratios, so power flows from stake, not rank (overview; see also pay ratio discussion). Buurtzorg (a Dutch home-care organization with over 14,000 employees) operates without supervisors or middle management and runs through self-managing teams (case description). Morning Star (a U.S. tomato-processing company) operates with no managers at all—employees negotiate responsibilities directly with peers (HBS case overview; also an overview of their self-management). Beyond business, Wikipedia and Linux show non-hierarchy at internet scale, where reputation and contribution govern authority (open source governance overview).

Again, I’m not claiming any of these organizations are perfect, but I think their examples can invite us to get curious about the power of connection and coordination rather than absolute control. In order to replace the habit of dominance hierarchy with relationship we need to get curious about the way we structure everything from business to politics—from basic questions like are we really a democracy if our president did not win the popular vote? (I don’t think so) to more nuanced questions like how does Swiss direct democracy interact with intertwines with federalism?

And why did anyone vote for Trump anyway? In addition to misinformation, I see two main issues: belief in dominance hierarchy and a lack of relationship. As anthropologist Daniel emphasizes on his channel WHAT IS POLITICS? the political right exists to uphold hierarchy—and even with all the propaganda that pollutes our political discourse—many people vote for Trump because they think they need an “alpha male” to keep society in order, a man like Trump who, as a sexual predator hoarding power and resources, would have been an ideal candidate for Maslow’s initial survey. And the second issue I see is a lack of relationship—in this case mostly white cis-identifying people lacking real relationships with minority groups and therefore mentally othering them as lower on the human hierarchy often subconsciously rather than consciously—because it stems from that habit of hierarchy and the most insidious habits are the ones that people don’t even know they have.

I’m not an expert in political theory, but I will link Daniel’s channel “What is Politics?” above that is helping me better understand true democracy vs dominance hierarchy and what we can actually do about it. I am a generalist and a teacher, our channel, The Unenlightened Generalists, is all about making connections and forming relationships between people and ideas, problems and solutions.

If you’re curious about how to build the habit of relationships in your own life—if you’re interested in forming non-coercive alternatives to punitive, hierarchical systems in your own families and schools and organizations, check out my next piece: Lord of the Lies, where I will explore ways to cultivate human instincts for mutual aid and cooperation from my experiences with restorative practices as a teacher.

I’ll just wrap up by inviting you to connect with each other—to use this crazy internet platform as an opportunity to have real connections in response to this essay. Where do you see the habit of hierarchy—how do you think we can or should kick this habit in our hearts and minds, in our individual lives and in our communities? I’d love to hear from you.

References & sources mentioned

- “Hierarchy” etymology: Etymonline — https://www.etymonline.com/word/hierarchy

- Great Chain of Being (overview): Britannica — https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Chain-of-Being

- Plato’s three classes (quick summary): SparkNotes — https://www.sparknotes.com/philosophy/republic/characters/

- Triune brain critique (popular-audience, authoritative): APA podcast w/ Lisa Feldman Barrett — https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/brain-myths

- “Adaptive brain” framing and quote source: Steffen et al. (2022), Frontiers in Psychiatry — https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.802606/full

- Maslow pyramid history (McDermid as source of pyramid depiction): Scott Barry Kaufman — https://scottbarrykaufman.com/who-created-maslows-iconic-pyramid/

- Ryan Heavy Head talk: “Naamitapiikoan: Blackfoot Influences on Abraham Maslow” — https://youtu.be/WTO34FLv5a8

- Additional write-up on Blackfoot influences and relational framing: Resilience.org — https://www.resilience.org/stories/2021-06-18/the-blackfoot-wisdom-that-inspired-maslows-hierarchy/

- “King bee” historical misconception (scholarly reference entry): Springer reference — https://link.springer.com/rwe/10.1007/0-306-48380-7_2057

- Hive “mind” / collective decision-making (popular science reporting on Seeley’s work): WIRED — https://www.wired.com/2011/12/the-true-hive-mind-how-honeybee-colonies-think/

- Buurtzorg self-management scale: Martela & Nandram (2025), Journal of Organization Design — https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41469-024-00184-y

- Let My People Go Surfing (audiobook): https://www.awin1.com/cread.php?awinmid=25361&awinaffid=1626919&ued=https%3A%2F%2Flibro.fm%2Faudiobooks%2F9781524752101-let-my-people-go-surfing

- Morning Star self-management (case overview): Harvard Business School — https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=45683

- Mondragón overview (incl. wage ratios and governance basics): Wikipedia — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mondragon_Corporation

- Open-source governance primer: Red Hat — https://www.redhat.com/en/blog/understanding-open-source-governance-models

- WHAT IS POLITICS? channel: https://www.youtube.com/@whatispolitics69